The recent news coverage relating to the fiscal cliff and taxes have died down a little in the past week or so, though it’s hard to forget how narrowly and inconsistently focused the discussion of it was. To be fair, I stopped listening at some point, but nowhere in any of it did there seem to be any hint of how taxes really work. In fact, most discussion used terms and language that foster a simply inaccurate conceptualization of the current tax system.

Now, I’m not going to say I’m an expert on taxes – I’m not. I’m also not going to to try to explain everything about taxes. All I want to do is clarify some simple things that you should probably know about taxes in as simple a way as possible. I plan to be pretty objective about this – I’m not saying taxes are good or bad, or that different types of taxes are better or worse than others. I’m just trying to let you know what they are.

I’m also going to just focus on individual taxes, as that’s what most people deal with. If you want to explain corporate taxes feel free to do it in the comments.

It’s also the case that I may get some things wrong – bear with me and feel free to correct me in the comments.

Sales Tax

I was planning on starting with sales tax because it’s something that you probably encounter more than any of the others. Like myself, you also might think that you have a pretty good idea of what sales tax is and how it works. Unfortunately, like myself, you may very well be wrong.

Sales tax, from a national standpoint, is actually fairly simple yet exceptionally complicated due to the nature of how rates are levied. From a consumer standpoint, you might know sales tax as something that simply gets added to your bill when you go to the store. If you don’t do a lot of traveling and you live in a place that doesn’t make some of the more nuanced distinctions you might even start to think that sales tax is fairly fixed.

Well, kind of. First off, each state gets to levy a tax, and each state does things a bit differently. We’ll call that the base state sales tax, and here’s what that looks like:

So the average base tax is right around 5%, though you can also see that a number of states don’t take advantage of state sales tax at all (those states – if you’re looking to plan your next vacation – are Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon).

Now, in certain states, that’s the end of it. In others, each county also gets a chance to levy taxes. Beyond that, some states also allow cities to levy taxes beyond that. You can imagine that there are a lot of these taxes, so I’m not going to go crazy on them right now – I may in a different post sometime though.

From a big picture perspective we can see the magnitude of some of these taxes by looking at the maximum sales tax rate in each state:

You can see that this is a little higher, though there’s still two states (Delaware and New Hampshire) that don’t levy any sales taxes even at these levels. While these rates are a little higher (with a mean of around 7.25%), we can figure out even a little more by looking at the paired differences between these rates:

So, you can see that 14 states are happy with the base rate and don’t levy anything further (among those are half of the M states: Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Michigan). Some states, like Alaska, do all their work at this level – Alaska is one of the states with zero base tax, but has a max tax of 7%.

That should be all of it, right?

Well, no.

Some states also make distinctions between different goods, the major categories being: groceries, prepared foods, prescription drugs, non-prescription drugs, and clothing. Some states exclude these items from general tax (29 states, for instance, exclude groceries from general tax), while some simply (!) tax them at a different (often reduced) rate. Illinois, for example, has a 1% base rate (instead of 6.25%) for groceries and both prescription and non-prescription drugs. At the same time, though, they have a increased base tax (8.25% instead of 6.25%) on prepared foods.

Confused yet? Yeah, this was supposed to be the easy part.

Like I said, I’ll probably come back to this one at one point, because there’s a lot of fine points here that are actually pretty interesting.

Vice Tax

Vice tax, or sin tax (not to be confused with syntax), is a subset of sales taxes levied against specific taxable goods which are seen or construed as socially undesirable. The most common targets of vice tax are products such as alcohol, tobacco, and firearms, though vice taxes are also levied against actions such as gambling, and other products such as other types of food or drink. In fact, the increased tax on prepared foods that I mentioned in the sales tax section is actually more likely and specifically classified as a vice tax.

These taxes function like sales taxes because they basically are sales taxes. The rationale (sane or not) behind them is that certain goods shouldn’t (or realistically couldn’t) be outlawed, but should be made to be just a little harder to get.

Well, a ‘little’ harder to get if you consider a ‘little’ to be somewhere in the 15-20 billion dollar range annually. If we assume that only half of the people in the country are sinning in any given year and that the number is closer to 15 billion that would work out to just under $100 a person, per year. If everyone in the country sinned in a year it would work out to just under $50 a person.

Other Use Taxes

“Use Tax” is the general term for things like sales tax that can be “avoided” by simply not using the products that are being taxed. Sales tax (and by extension vice tax) is a use tax because if you don’t want to pay it you aren’t obliged to actually purchase anything that carries it. If you went totally off the grid and built your own house, grew your own food, etc, you might be able to get away without purchasing anything that carried use taxes.

The argument that certain things (like groceries) are necessities to life is part of the rationale behind why certain states exclude those items from general sales tax. If you live in, for example, Maine, you can live off the sales tax grid but still buy groceries.

The majority of use taxes fall into sales tax and are covered above, but there are some things that are not called taxes but function similarly. The example that I want to cover here is tolls on state owned toll roads.

Now, if you live in a state like Illinois or Indiana or Ohio or Pennsylvania or New England, you might be familiar with toll roads. If you’re not, the idea is simply that drivers pay tolls when they drive on toll roads, based on the distance traveled. This revenue is often used to upkeep those roads.

A rose is a rose by any other name, and such holds for taxes as well. Like “true” use taxes, tolls can be avoided by simply avoiding toll roads. I’m sure this isn’t the only case where a tax moonlights as something else, so I’d be interesting in hearing if people can come up with others.

Property Tax

If you want to vote in an election in 1855 North Carolina you had best own some property. If you’re a bit more ‘present’ focused, owning property these days will most simply and reliably help you owe some property taxes.

Property taxes are pretty much what they sound like – taxes levied by a jurisdiction on property. The amount of tax paid is based on a fair valuation of the property in question. This fair valuation is often first carried out by the property owner, though the taxing authority has the right to formally value the property via a tax assessor if they so desire.

If you thought that sales taxes are levied by a lot of different authorities, spend some time on Google trying to figure out the size of a ‘jurisdiction’ in relation to property tax rates. It appears that any authority able to pass referendums or millages carries jurisdiction over those areas to which those apply, and it is through these millages that property taxes are generally fixed (or changed).

What this means is that there are a lot of property tax jurisdictions in the United States. More than sales tax jurisdictions, it would seem, which precludes doing any sort of more complex analysis without considerable effort.

Estate and Gift Tax

Estate tax, put simply, is a tax levied against the transfer of wealth from a deceased to the beneficiaries of the estate of that deceased. The gift tax is tied to this due to the ability to avoid the estate tax by simply ‘gifting’ away all your stuff before you die. For simplicities sake we can consider them one in the same – a tax levied against person to person (we could also call it peer to peer and then make it P2P) transfer of wealth and/or capital without the reciprocal transfer of goods or services (which would then cover such a transfer with sales tax).

So why not just buy a boat and give that to your kids? Or ten boats? Well, let’s overlook the fact that boat depreciation might actually devalue your estate to the point that taxes are appreciably less, and instead focus on the fact that this isn’t a tax on money alone, but on wealth via the estate. Houses, boats, cars, copies of Marvel Comics #1, etc. There’s a lot of complexity here, but I’m going to try to keep it as simple as possible.

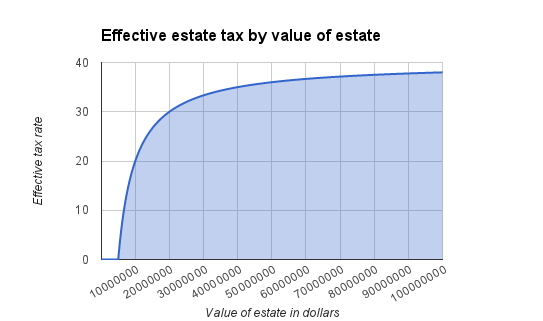

You might not be familiar with estate tax, even if (or especially if) you’re recently deceased. The reason for this is some fairly high thresholds set for excluded wealth. As of 2013, the first 5 million dollars of an estate’s worth are exempt from federal estate tax. Beyond this, the estate is taxed at 40%. The graph that this produces should hardly be surprising by now:

Income Tax

Some of you might recognize that I’ve talked about income tax before. Yes, I’m going to recycle some of that content.

Income tax is really where a lot of the misinformation comes into play when people are talking about taxes. Part of the problem – it would seem – is that income taxes seem simple enough (they’re taxes levied against your income) that people constantly make their own assumptions about how they work. These assumptions are further substantiated by the language used by a large percentage of those who describe income taxes.

Anyway, let’s get to it, shall we?

One of the main components of income tax – and perhaps the most discussed – are income tax rates.

Tax rates are the percent of your taxable income that is paid in taxes. Here are the tax rates for 2011 (from http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/i1040tt.pdf)

| Tax Bracket (Marginal) | Married Filing Jointly | Single |

|---|---|---|

| 10% Bracket | $0 – $17,000 | $0 – $8,500 |

| 15% Bracket | $17,001 – $69,000 | $8,501 – $34,500 |

| 25% Bracket | $69,001 – $139,350 | $34,501 – $83,600 |

| 28% Bracket | $139,351 – $212,300 | $83,601 – $174,400 |

| 33% Bracket | $212,301 – $379,150 | $174,401 – $379,150 |

| 35% Bracket | Over $379,150 | Over $379,150 |

This table has a lot of information in it, and one of the things that gets a lot of people confused about taxes is what exactly these tax brackets mean. There are a lot of people who think that crossing into another tax bracket means that your entire taxable income is now taxed at that higher rate. That’s not the case. If this is the only thing you take out of this post that is the thing you should pick up on. Here’s how it works.

For simplicity’s sake, let’s say you’re filing your taxes as a single person, not a married couple.

Let’s say you make $5,000 taxable income. That income is taxed in the 10% bracket, and you end up giving the government $500 (10%). Now, let’s say you have a friend who is about twice as well off as you, and makes $10,000. That falls in the 15% bracket, so it should be 15% of $10,000, or $1,500 right?

No. This is the main misconception of taxes. People do not fall into tax brackets. Their money does.

The above is not the rate that a person pays in each of those brackets – it is the amount that the money you’ve made in each of those brackets is taxed. This is the idea of a marginal tax code. Got that? Here’s a graphic to give a better idea of this:

Much better. Now, imagine that every time you make a dollar over the course of a year you throw it into this big multicolored bucket that you keep in your garage. You start out the year with your first bit of income, and throw it in the bucket. As long as you’re filling up that very bottom blue section your income is being taxed at 10%. Pretty nice.

Now, that blue section can only hold so much money, and after a while (about $8500) you can’t stuff another dollar in it no matter how hard you try. Now you have to start filling the red section of the bucket.

Every dollar you throw into the red section is getting taxed at 15%, but the dollars in the blue section have already been taxed at 10%. The tax you pay on those dollars doesn’t change, only the money that you continue to make.

You’re having a good year, and pretty soon the red section is filled up, too. Bummer, the yellow section is taxing at 25%. Oh well, by the time you’ve filled it up you have just a little less than $79K profit, even after taxes.

I think you probably have the point by now. You keep filling up sections until they’re full, then move onto the next. Now, the top light blue section only goes to $500,000 in my graph, because I didn’t feel like making an impossible graph. You see, that light blue section goes on forever.

Thus, when people talk about how the highest tax rate used to be in the ballpark of 90%, what they’re talking about the highest marginal tax rate. What that does not mean is that anyone ever payed in the ballpark of 90% of their income (though I suppose if you made enough money it could get close), but rather that after their income crossed some threshold any additional income was taxed at that rate. Once a dollar is in the bucket and taxed at one rate that dollar is done. The first dollar that anyone makes in a year is always in the first tax bracket (unless it’s an exception and not in any bracket).

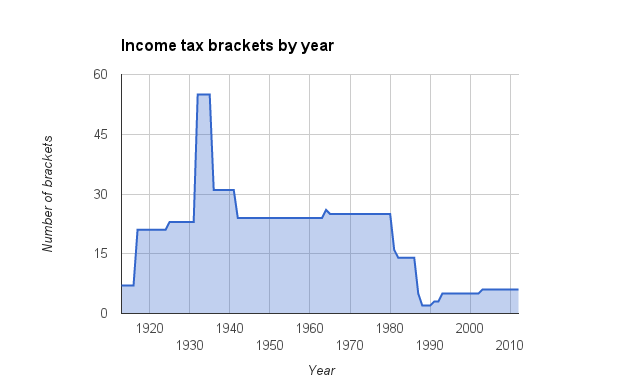

The trick is also that there used to be a whole lot more brackets (sections of the big multicolored bucket). In fact:

Those numbers are correct – back when the top rates were really high there were also a lot more brackets. These top brackets were sometimes referred to as ‘millionaire tax’ and were meant to set realistic caps on the amount of money that individuals could earn annually. A number of brackets were added at the start of the Great Depression to help control the economy, and then slowly phased out during the rest of the Great Depression. The number of brackets was pretty constant from the end of WWII to the 80s, when things were brought down as low as two brackets.

Now you understand taxes. Well, simple taxes.

I’ve been trying to keep semantically consistent and use words like ‘taxable income’. Everything that we’ve talked about so far is based on the fact that you make X number of dollars each year. The tax code isn’t quite so simple, though, and the other driver of how much you pay in taxes are deductions.

What does a deduction or exemption do? Put simply, it deducts or exempts dollars from your taxable income, or exempts you from part of your tax burden. Do you know what that means? You sometimes don’t have to throw those dollars into our multicolored basket at all.

If I still have your attention, great! We are almost there.

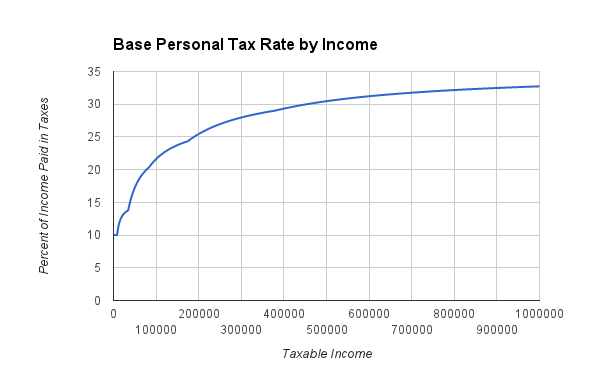

If you end up saving some of the money you make from going in the bucket, or even if you don’t but if you make more than $8500 a year, then you’re not paying any standard fixed rate of tax, but rather an effective rate that’s specific to your situation.

The effective tax rate is different for everyone, and is a bit trickier to figure out based just on income. It’s this effective tax rate where much more subtle changes can be made. The overall tax rate can be put in a little table, and it’s pretty easy to conceptualize and understand. Changes to that are things that you can explain away in soundbites on 24 hour cable channels. You can probably picture that table showing up as a nice simple graphic.

Changes to the effective tax rate take a bit more garrulousness.

Want to know what your effective tax rate is before any deductions and/or exemptions? It’s a piecewise function, and without belaboring the point here’s what it looks like:

There’s actually a great discussion of asymptotes and limits to be had here, but that’s not for today. What you should take away is that no person will ever pay 35% of their income in taxes under the current tax policy. While some of their money (the more they make, the greater proportion) will be taxed at 35%, they always had their first $379,150 taxed at lower rates.

If you’re curious, the formula you should use to figure out the taxes someone should pay if they make more than $379,150 is:

850+3900+12275+25424+67567.5+((TAXABLE INCOME-379150)*.35)

If you’re inclined to math you can also probably figure out how to modify that pretty easily to any income level. If you’re not inclined to math perhaps you should take the time to figure this one out as an exercise. =)

Anyway, that should give you a good base to start with if you’d like to get into any conversations about taxes. Keep in mind a few simple facts and you won’t find yourself being tricked over and over by misleading wordings.

Hi. Interesting post. Do you have a public profile or bio that you wish to share? I don’t see a link for it here.

I am most interested in public ignorance of income taxes. I made this tool to help educate: http://mindtools.net/Taxes1/

I think people should think in terms of effective taxes rather than the brackets, which cause nothing but confusion.